Through photos and artifacts, Operation New Life exhibit tells untold stories

- Admin

- Jul 3, 2025

- 3 min read

By Ron Rocky Coloma

Marissa Ko didn’t know about Operation New Life before she began working on the exhibit. But once she stepped into the research, the stories pulled her in. Not the official ones from military memos or government briefings. The human ones. The kind tucked behind photo negatives or whispered across decades.

“As someone who was unaware of Operation New Life before working on this project, I was eager to learn as much as I could about the operation,” Ko said.

Her curiosity led to a different kind of exhibit—one built not around long wall texts, but around donated photographs, artifacts and memory. Visitors don’t walk into a history lesson. They walk into a space that invites quiet observation, and sometimes, conversation.

“There’s a small placard for every ‘cluster’ of pictures we have that gives a relatively informative explanation,” she said. “But apart from that, there’s not a lot of signage.

Instead, we give full guided tours upon request. A majority of visitors usually take themselves through the exhibit, but a number of individuals have been willing to share stories that they remembered as they walked through.”

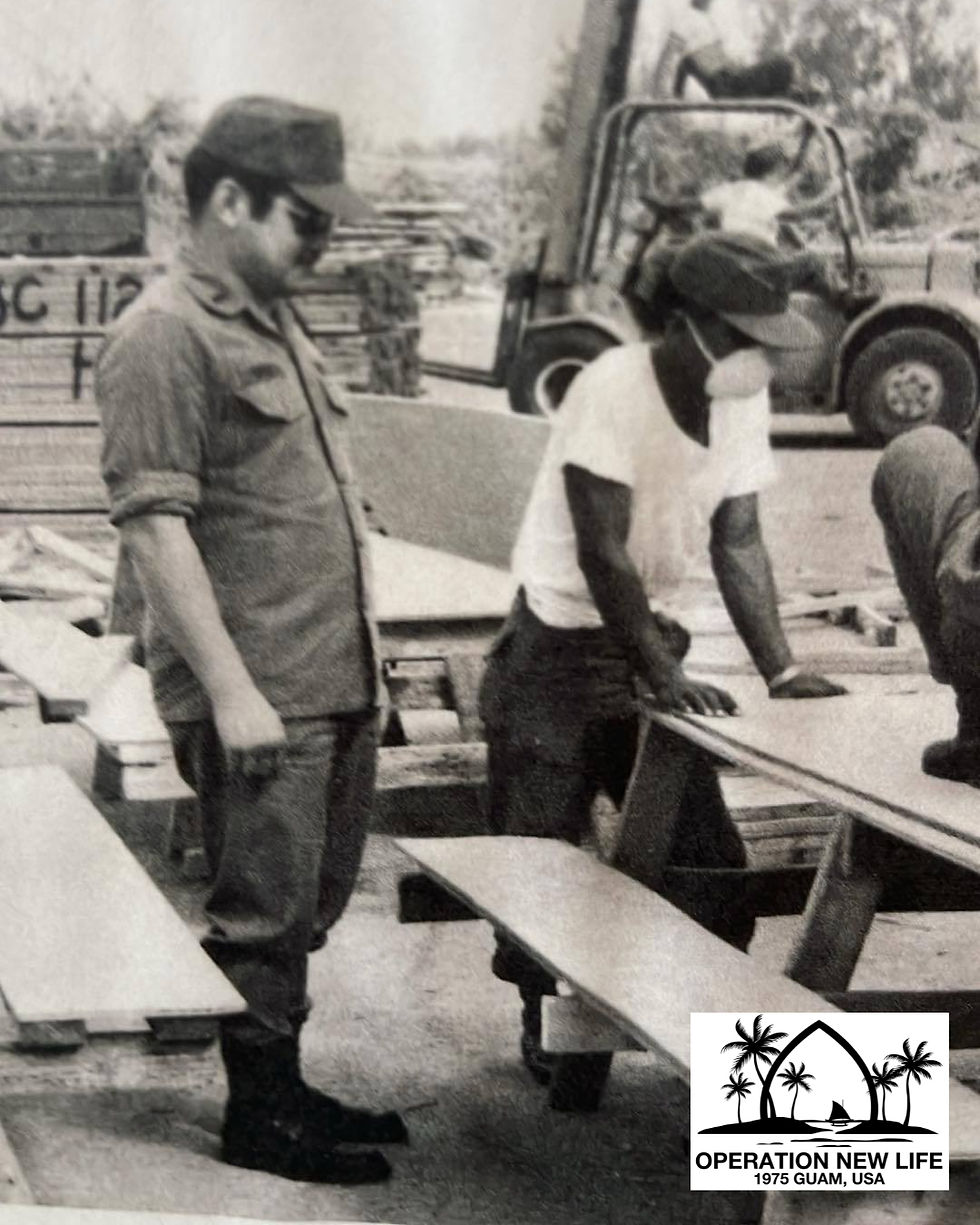

The exhibit centers Guam’s role in housing more than 100,000 South Vietnamese refugees in 1975—part of the largest humanitarian evacuation of the Vietnam War. While much of the global focus has been on the political and military aspects, Ko and the team, led by Dr. Nam Kim, wanted to shift the narrative.

“Through all of these pictures and artifacts, we want people to recognize and hear these refugees and others involved in the operation, and their stories that have been previously pushed to the side as an afterthought of the Vietnam War,” she said.

Some moments stayed with her. A man once walked up to the desk and told her about a bus full of refugee children that had broken down at his old auto shop.

“When they heard the sounds of airplanes flying overhead, they were terrified and scrambled for cover,” Ko recalled.

Another time, she found a set of negatives hidden in an envelope, tucked between photographs waiting to be archived.

“When I held some of them up toward the light, I saw some pictures that I had never seen before, and I could just feel my heart start racing with excitement,” she said.

Those discoveries underscore what Ko hopes the public takes away. Not just awe for Guam’s role in the operation, but also for the resilience of the refugees who fled their homes, often not realizing they would never return.

“I hope the main emotion and conversation that sparks would be some form of awe for the fact that one of the biggest humanitarian aid events occurred on

Guam, and the hospitality of Guam was in full display,” she said.

That hospitality echoes through every image. Military wives handing out food. Navy seamen playing basketball with refugee children. A Red Cross volunteer holding a baby.

Guam, Ko said, was more than just a strategic outpost. It was a sanctuary.

“I think Operation New Life is one of the best examples we have,” she said. “Guam may be small, but it has been a significant place for thousands across the world.”

Balancing logistics and emotion hasn’t always been easy. The team has had to weigh what to include, how much detail to give and what language to use when presenting trauma to a public audience.

“There is a lot of double-checking with Dr. Nam and our volunteers about things we could or could not mention,” Ko said. “A lot of them were involved with Operation New Life and/or the Vietnam War one way or another, so they have been crucial in the process of telling this story of trauma and resilience to the greater public.”

Still, for Ko, one theme stands out.

“That there is a worldly kindness to Operation New Life,” she said. “Especially at a time like this, it’s crucial for people to understand that there’s hope in communities that come together and care for each other.”

And that story, she said, is far from over.

“There’s a lot of stories that still remain—and will remain—untold,” Ko said. “But that’s the beauty in this line of work. We will keep listening for stories.”